Simply Writing

Scripts That Few Could Read

The exhibition is the fruit of collaboration between the Museo Diocesano di Benevento and the Biblioteca Capitolare belonging to the Capitolo Metropolitano “Santa Maria Assunta” and the municipality of Benevento.

Its subject is communication within the church at Benevento between the 8th and 14th centuries.

As is well known, one of the consequences of the migrations of the Germanic peoples, the dissolution of the Western Roman Empire, and the establishment of the Roman-Germanic kingdoms, was the destruction of the Roman education system. There was a progressive reduction in the number of literate people, and a radical change in the way written documents were produced, with the disappearance of lay workshops.

From the 7th century onwards, writing and reading became increasingly important and ubiquitous in the monastic and ecclesiastical world; activity linked to manuscript production was gradually concentrated in the scriptoria that arose within religious institutions.

Cathedrals, abbeys and monasteries became the almost exclusive centres of text production.

Bishops and ecclesiastical and monastic elites soon realized the difficulty of communicating the biblical message to the illiterate; the traditional written text could perform its function only if accompanied by illustrations, symbols or figured images.

For the exhibition illustrates three different modes of transmission of the message (writing, symbols and images), exemplified by codices in Beneventan script, photographic reproductions of panels from the bronze door of Benevento cathedral, a wooden reliquary, a box of bronze sheet, and lastly a facsimile of the roll Exultet.

Date:26/01/2019 – 30/06/2019

Region: Campania

Town: Benevento

Subject: Writing

The “Lombards in the Limelight” project was organized to make known to a wider public the museums of the seven towns in the serial site (Cividale del Friuli, Brescia, Castelseprio-Torba, Spoleto, Campello sul Clitunno, Benevento, Monte Sant’Angelo), in collaboration with one another and several national museums with Lombard/Early Medieval sections.

This encounter involves 7 exhibition themes, which are divided between the 13 museums listed below.

Biblioteca Capitolare di Benevento

The capitular library is the archive of the urban chapter of Benevento cathedral, which over the centuries evolved into a library. It houses numerous extremely rare manuscripts and codices, the oldest of which is an edict issued by the Lombard prince Radelchis II in AD 898.

Museo Diocesano di Benevento

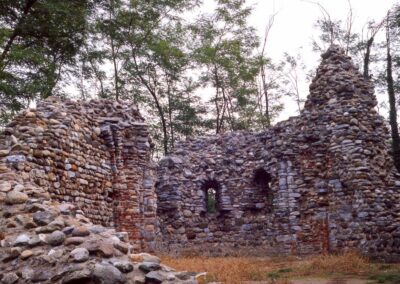

The museum of the diocese of Benevento features an underground archaeological itinerary and an exhibition area with a “pseudocrypt” founded in the 5th century containing numerous precious objects dating from the 6th to 14th centuries.

The huge cathedral of Benevento is crammed with people, yet silent.

A young deacon steps onto the pulpit and turns towards the crowd.

His head is upright, his eyes look upwards, his voice clear. He intones the Exultet, the Easter prayer to the Lord. The crowd before him is enraptured by the chant. The syllables overlap one another, merging into a hypnotic dirge of Latin words that the people hardly understand. In the cleric’s hands, however, there is something that people can follow: a scroll that the young man slowly unrolls, to the rhythm of the chant. The word of God becomes an image: powerful and authentic. The syllables come to life, miraculously.

They were hungry for images, the Lombards.

They were a pagan nomad people, who had travelled countless miles through forests and steppes before arriving in Italy.

Their imaginary world had been formed by watching the shadows spread over the woods, the fish darting in the riverbeds, the sea sucking the waves into eddies, and the lightning exploding in the sky, unleashing huge storms. The words on the sheet were not letters and sounds, but spells that evoked landscapes, events and people.

For the Lombards words were not words, they were visions, and the new language they brought to Italy was made of powerful images.

Their Germanic dialect survived for a while, absorbed by the Latin that they adopted quickly. But their visions did not: they turned into sculptures, drawings, relief carvings. Every chapel was not stone, each reliquary was not an object, they were stories.

In their minds everything was constantly transformed into something else. The word of Christ became flesh, and Christ himself was not 121 distant and abstract, he was a human body, but also an animal in nature, a seahorse that guided hoards of fish, or a spring gushing in the desert. Not a metaphor but an example: eternity become tangible, like a snake biting its tail in an infinite circle of past, present and future. Uncultivated writings, those of the Lombards. Fantasies born of their human adventures, transformed into powerful images.

They were fixed to the pages and finally turned into letters and sumptuous manuscripts, suited to the refined courts of their dukes and kings. Elegant and direct, like everything that flows from the experience of a people who created history

Mariangela Galatea Vaglio