Longobards in Italy

Upon their arrival in Italy the Lombards came into contact with the culture of a land that had become a strategic crossroads between West and East, once the heart of the Roman Empire and now the centre of Christianity. Their settlement in Italian territory led to contacts with the local population, resulting in a slow process of integration that gave birth to a new culture that harmonized Germanic traditions with Classical and Roman-Christian traditions.

The relationship with antiquity thus created was exploited by the Lombard elites to legitimize their growing power. In fact, today the Lombards are attributed a decisive role in the transition between Classicism and the Middle Ages: they contributed to developing and spreading the cultural, artistic, political and religious advancements that spread from Italian lands, anticipating the cultural renewal attributed to the Carolingians.

The Lombard kingdom in Italy

In 568 the Lombards, led by Alboin, arrived in Italy from Pannonia; they were a fighting people led by an aristocracy of knights and a warrior king chosen from the ranks of the army. After occupying Friuli, they gradually extended their domain over most of Italian territory, establishing a kingdom able to oppose the Byzantine dominion. The Lombards ruled all of north Italy except for the coastal areas of Liguria and Veneto; the duchies of Spoleto and Benevento were established in the centre and south.

The Byzantines held on to the territory of the Ravenna Exarchate and the “Byzantine corridor” that connected Ravenna with Rome and divided the Lombard kingdom into two parts: Langobardia Major in the north and Langobardia Minor in the south. In 572 Pavia became the kingdom’s capital, but for another a decade Lombard dominion was controlled by the numerous duchies, which enjoyed great autonomy.

The Lombard duchies

The cities where duchies were based basically became the centres of military control of the surrounding territory. The countryside, however, was organized into rural zones managed by arimanni (free soldiers) who, in addition to military aspects, took care of the economic and productive resources using indigenous peasant labour.

With the consolidation of Lombard power, the political structure based on duchies was strengthened: each duchy was led by a duke, who was a royal official with public powers, assisted by lesser figures such as astalds (appointees of the king, judges, notaries) and in the 8th century, gasinds. From being the military leader, the king gradually evolved into a sovereign able to institutionally represent his entire people in relation to the Byzantine empire, the papacy and the Franks. From military occupation force, the Lombard kingdom was transformed into a state with a differentiated society and a hierarchy linked to land ownership.

Era of the great sovereigns

From the 6th to 8th centuries, great sovereigns such as Authari and Agilulf, Rothari and Grimoald, Liutprand, Aistulf and Desiderius gradually extended royal authority, strengthening the internal unity of the kingdom. The peak of Lombard political power was reached under Liutprand (712-744): he increased the kingdom’s territory, reaching the gates of Rome and subjecting the still independent duchies of Spoleto and Benevento; he also knew how to contain the Papacy and pursued a Europe-wide policy, strengthening links with the Franks and Avars. Unfortunately, with the conquest of Ravenna in 750, Lombard expansionism upset the delicate political balance in the peninsula. The Papacy asked for assistance from the Franks, who in 774 defeated the Lombards, incorporating (without eliminating them) all the duchies into the Carolingian empire. Only Benevento, elevated to the rank of principality, retained its autonomy until the Norman conquest (1076).

Society

Lombard social structure was based on the farae, military aristocratic clans, at the head of which there was a duke who commanded the arimanni, free men belonging to the aristocratic class who were linked to him by kinship ties. At the base of the social scale were the serfs who lived in conditions of slavery, while at an intermediate level were the aldii, semi-free men who carried out military service as infantry soldiers, archers and squires.

In Italy the farae remained culturally distinct from the Byzantines and Romans, preserving their own traditions. Initially, this made their relationship with local populations difficult and violent, but the situation changed over time due to conversion to Catholicism. The Lombards began to integrate with the old Roman elites, who gradually accepted their presence. The last Lombard kings, Liutprand and Ratchis, intensified their efforts for integration, presenting themselves increasingly as king of Italy rather than king of the Lombards.

Daily Life

From clothing to religion, and diet to agricultural and commercial activities, over the centuries the Lombard people were on one hand protagonists of numerous cultural integrations with the Byzantines, and on the other hand brought innovations typical of their Germanic origins to the land in which they had settled.

The result was the birth of a new cultural community that underwent various social modifications, without ever losing its traditions completely. Even today we can recognize signs of this passage: an example is the cult of St Michael, the archangel “warrior of God”, who became the patron saint of the Lombards because they recognized in him the pagan god Wodan, protector of warriors.

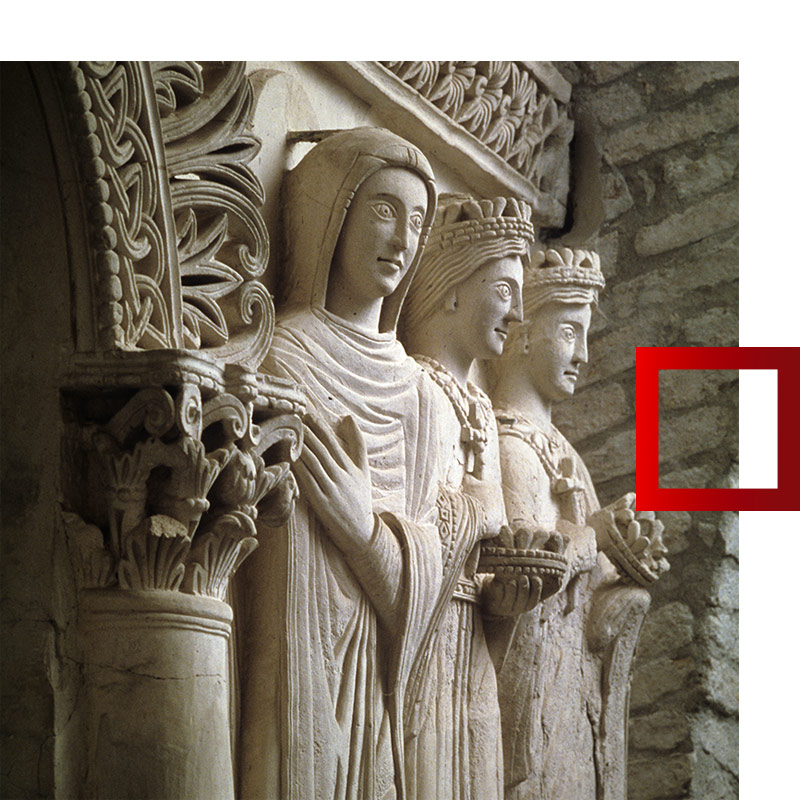

Architecture

The Lombards did not have their own architectural, pictorial and sculptural traditions but made use of the existing craftsmen in the area. This is one of the reasons why Lombard artistic manifestations in Italy are highly diversified, with specific characteristics in the various parts of the kingdom. There was a clear desire to standardize all the monumental complexes, but at the same time we see a variety of artistic results.

We also find in many monuments a predilection for prestigious architecture represented by the monuments of the northern duchies. Among the best preserved examples are the church of San Salvatore in Spoleto and the Campello sul Clitunno ‘Temple’, exceptional buildings for the classical Roman style with which they were both designed.

Famous Lombards

There are numerous Lombard personages who have gone down in history; of particular note is Adelchis, son of Desiderius and Ansa, whose name is linked to the tragedy written by Alessandro Manzoni which tells of the historical events related to the war against Charlemagne.

Other important names are Alboin, the king who conducted the Lombard people from Pannonia to Italy and led the conquest of the kingdom, Theodelinda the Catholic queen who contributed to the construction of numerous churches, monasteries and new residences, and Paul the Deacon, the monk who wrote “Historia Langobardorum“, an epic work which relates – and has handed down – the deeds of the Lombard people

Assessing the Lombards

For centuries historians have debated the so-called “Lombard question”, which regards the effects of Lombard dominion in Italy.

Over the years, the Lombards have been evaluated in contrasting ways: for some, they were a few “barbarian” invaders who undermined Classical – the only authentically “Italian” – civilization; for others, an already Romanized people who attempted to create a new and united nation.

These judgements are loaded with various meanings and rooted in attempts to explain historical circumstances and events.

In the 14th century the Viscontis, in support of their expansionist policy, chose them as their mythical forebears, while the 18th century followers of the Enlightenment saw in the Lombards the first real opposition to the Church’s interference in secular matters.

Historians today view the Lombards as part of a long “transition period” which led to the formation of European nation-states.